give inmates addiction treatment

season 1 Episode 5: the jail turns things around

SOLUTION:

Make incarceration an opportunity to get help and start healing. Make detox easier, get people with addiction drug treatment behind bars, and connect them to help as soon as they’re released.

STORY:

Opioid withdrawal is like the worst flu you’ve ever had. Now, imagine you’re responsible for dozens of people as sick as can be. What do you do?

We tour the Snohomish County jail, which has become a defacto detox center and where inmates used to die from lack of medical care. The jail turned things around and today they’re trying to make the jail a place of healing.

This season we’re in Snohomish County, Washington which has an oversized share of overdose deaths in the state and is now treating the opioid epidemic like a natural disaster.

LINKS TO MORE INFORMATION AND RESOURCES:

Snohomish County overdose and addiction treatment resource guide.

An article on other jails across the country that use medication-assisted treatment do it too.

More about the Rhode Island prison system’s comprehensive approach to opioid use disorder, which helped decrease the state’s overdose death rate by 12 percent in one year.

Research: Treating inmates’ addiction behind bars can be effective in helping them continue drug treatment after they’re released.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse presents evidence in support of using medication to treat inmates’ opioid addiction.

Research: Detroit found heroin users spent about $60 dollars a day on average on drugs.

TRANSCRIPT

TRANSCRIPT OF FINDING FIXES: EPISODE 5

(Click the play button at the top of this page to listen)

Anna Boiko-Weyrauch: That’s the sound of a jail door closing behind me. I’m in the Snohomish County Jail in Everett, Washington.

The heavy, remote-controlled door between units at the Snohomish County jail.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH / FINDING FIXES. >>

Anna Boiko-Weyrauch: Folks from the county are leading me on a tour. I’m seeing how they handle so many inmates addicted to heroin.

In the medical ward, we run across a young man with thick black wavy hair. His face looks unnaturally ashen. He sits slouching forward on a bench. He’s wearing a green and white striped uniform, he’s an inmate and he’s really sick.

A nurse, Julie Farris, leans over.

Julie Farris: How much heroin are you doing a day?

Boiko-Weyrauch: She asks him how much heroin he usually does.

Man: A couple grams a day.

Farris: A couple grams a day? Have you gone through detox before?

Man: Yeah.

Boiko-Weyrauch: He tried a program that uses medicine to replace heroin. Suboxone. His voice is hoarse.

Farris: A suboxone program? Did you stick with it?

Man: I stopped doing it two weeks ago.

Boiko-Weyrauch: But he stopped.

Farris: How come?

Boiko-Weyrauch: He looks up and sort of shrugs.

Man: Heroin.

Farris: Yeah, I get it. I get it. Okay.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Heroin. A one word answer that explains everything. Nurse Farris takes the stethoscope from around her neck.

Farris: I got 130 over 90. So what that’s saying is your blood pressure is pretty good. But we need to get your stomach taken care of. Does that make sense?

Man: I’m so hot.

Farris: I know. I know. Let’s repeat his temperature. All right, so the thing is you’re getting a little dehydrated so we get to some fluids and you’ll start cooling down. Okay? So because you're throwing up we need to put it in your bottom.

Man: I’m so thirsty.

Farris: I know, I know. I get that. I get that. So we get another 30 minutes after that, then we’ll try some sips. We’re going to give you some chicken broth to help your stomach and then get your guts settled—a little bit of a rest. Does that make sense?

Boiko-Weyrauch: He starts crying and slowly droops forward. The young man is puking everything up, so they have to give him a suppository with medicine to stop him from vomiting.

Farris: I know. I know. Hang in there man.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Nurse Farris helps him stand up and grabs a fistful of his uniform on his back—to keep him standing up.

Farris: Come on. We’re going this way.

Inmate slippers.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH / FINDING FIXES.

Boiko-Weyrauch: They walk into a cell and out of view.

Withdrawing from heroin is like the worst flu you’ve ever had. You get it bad out of both ends. The Snohomish County jail has been flooded with people in just this situation. People addicted to opioids are getting arrested, booked into jail, and then withdrawing.

Some inmates were even dying—they weren’t getting the medical care they needed. From 2010 to 2014, over a dozen inmates died. Two from drugs, many from medical complications and some from suicide. The families of these inmates sued, and the county has paid millions in settlements

The jail has turned things around, and inmate deaths are rare now. And recently, the jail is handling inmates with addiction differently than they used to. We’re going to tell you how.

This is Finding Fixes–a podcast about solutions to the opioid epidemic, I’m Anna Boiko-Weyrauch.

Kyle Norris: And I’m Kyle Norris. In this episode, we’re talking about solutions in and out of jail. We’re gonna look at how to help inmates detox more humanely. And connect them with treatment and services as soon as they’re released

Boiko-Weyrauch: I’ll be guide this episode. Let’s start downstairs in the jail’s booking area. This is where officers bring inmates after they’re arrested.

The jail is strained by the number of people coming in addicted to opioids. There are regularly more inmates needing medical care than there are beds for them.

So much so, they have to make some uncomfortable choices

Ryan Saunders: Well, what we do is we get the paperwork from the arresting officer.

Boiko-Wyerauch: Ryan Saunders is a booking support officer. He’s sitting behind a tall desk at a computer, and he’s wearing a uniform and some really stylish glasses—like a hipster Buddy Holly. Saunders tells me something surprising.

Saunders: Since we’re the, kind of, first face that the officers see. They ask us a lot of times what the population’s like upstairs. In our medical housing—our observation unit. And they kind of look at us to know if we are full, we have a little bit of space left over. So we're kind of sometimes the bearer of bad news as it were for the arresting officer when they're coming in with an arrestee and we tell them, you know, “Hey, this is a misdemeanor charge, we’re packed up stairs, we don't have the manpower to cover it so the chances are they're probably going to get kicked.”

Boiko-Weyrauch: What’s kicked?

Saunders: Sent out.

Boiko-Weyrauch: I didn’t realize his job might include turning some people away from jail. The reason is, the jail doesn’t have the staff or space to deal with these inmates detoxing here.

Saunders: We’ve had illegal camping warrants where they set up a tent somewhere, behind a Safeway or something. And it’s such a minor charge that it’s almost not worth it to deal with taking them up there, having the manpower to keep them medically good upstairs and then have them go to court on something that’s a $200 warrant.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Four years ago, the sheriff changed the rules on who gets booked into jail. No more people arrested on non-violent misdemeanors who had big medical or mental health needs the jail staff couldn’t handle.

Saunders says burglaries and DUIs are still getting booked though. And, if you’re running around in traffic and making a nuisance, they’ll find space for you.

Saunders: But unfortunately a lot of the time, if we’re full upstairs, we’re full upstairs.

Boiko-Weyrauch: What do you make of that?

Saunders: I think it's a bummer. I mean really. Perfect world, you know, if you get arrested on something to come in, you get booked. In a perfect world.

Boiko-Weyrauch: In a perfect world, if you come into jail you stay in jail?

Saunders: Right, right. You know, kind of the way it used to be before this really god awful epidemic has hit us. It’s unfortunate that it’s come to this.

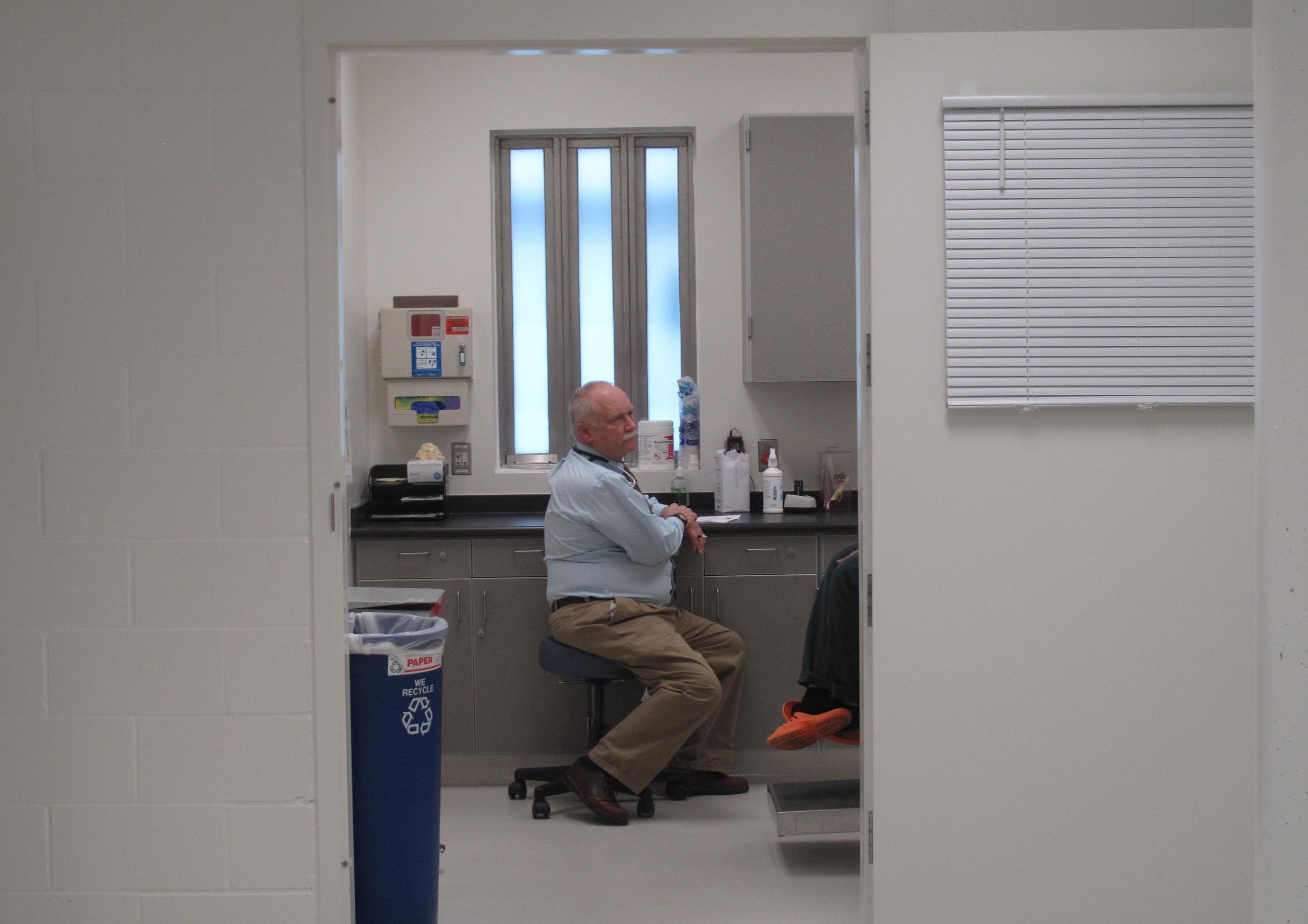

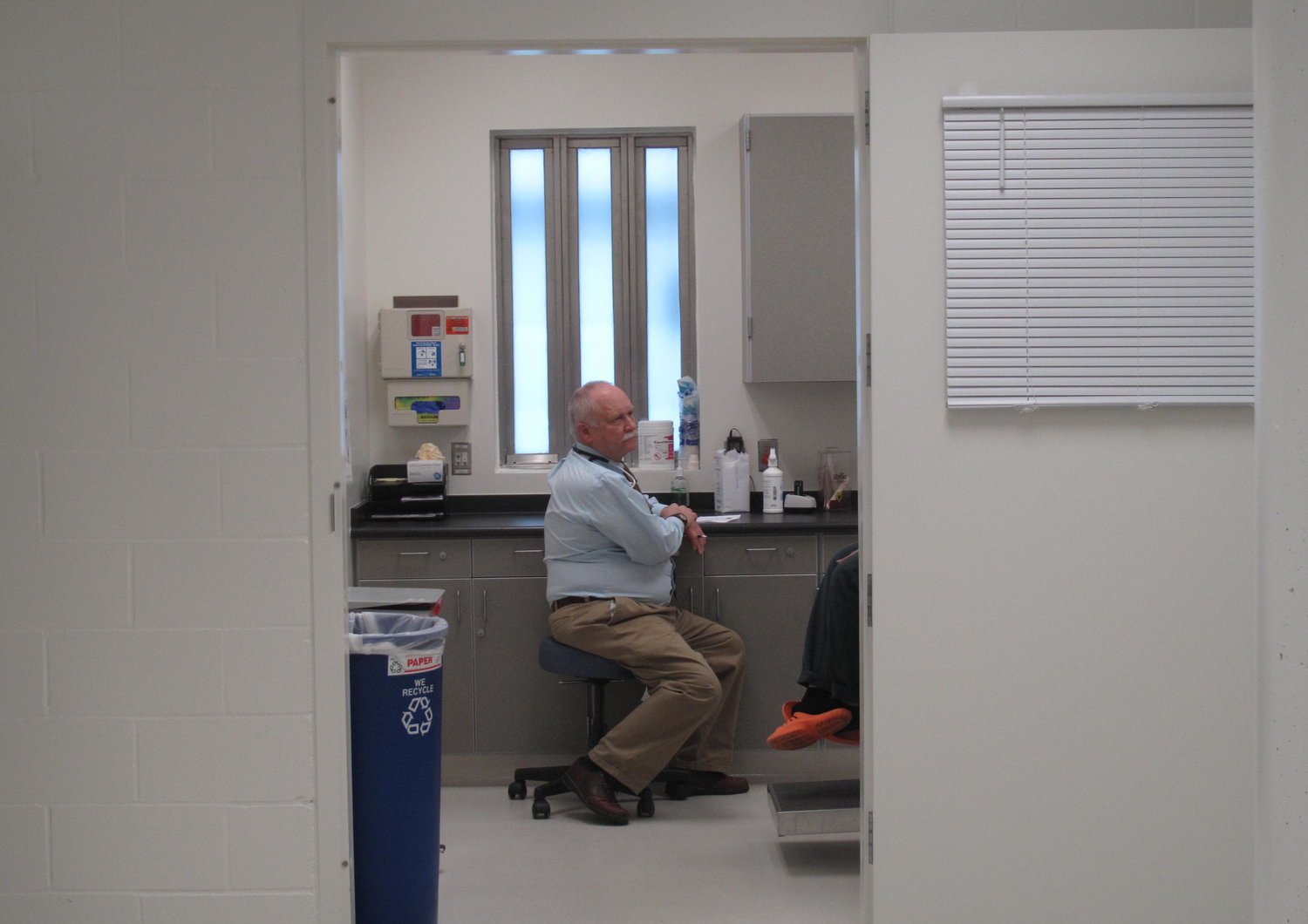

Medical Staff in the Snohomish County Jail.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH/FINDING FIXES »

Boiko-Weyrauch: Shari Ireton, with the sheriff’s department, is one of my escorts around the jail today. She has something to say about this, on behalf of her boss

Shari: It’s frustrating for leadership like the sheriff, he knows the pain and the pressure the community feels when you have somebody wreaking havoc in the neighborhood stealing bicycles spray painting garages—it's frustrating. But when he became sheriff and started looking at the data, he also realized that arresting them cycling them in and out of the jail wasn't working either and it's putting a lot of pressure on this facility and to have thirty, fifty—you know—sixty inmates all detoxing, taking up a lot of resources in the jail for stealing a bicycle, right? Because we have folks in here who have committed felonies who are definitely going to come in here and stay here and we have to treat them as well.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Upstairs in the medical ward, the Upstairs we’ve been talking about, nurse Julie Farris has seen the changes in the jail herself.

Farris: Thirteen years ago we used to have ninety eighty to ninety nine percent alcoholics coming through our doors those days are gone and now we have their kids or grandkids coming in and now it's heroin. And heroin is just sapped our community it's killing our children and...I'm going to get emotional.

Boiko-Weyrauch: This topic hits a nerve.

Farris: Heroin is stealing our children from us and stealing their lives from us and we have to do something because our children it's our future and if that's this is our future we're lost. As a community we have to do something.

Boiko-Weyrauch: The thing about opioids, it’s not just young inmates who end up in the medical ward, either.

This is a little jarring:

Farris: It's not uncommon to have sixty two year olds coming into the jail now that have started heroin because they have the chronic pain needs but their doctor says, “Oh, you're addicted to it” and they'll cut them off—straight off.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Sixty-two year olds coming in to the jail who are addicted to heroin?

Farris: Yes we have that. It's not uncommon. It’s sad to see 60-year-old people coming because they’re withdrawing.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Back in 2015, they would have so many people withdrawing, the medical ward would fill up. So, the jail had to open up a new module—that’s the term they use for a cell block—open up a new module and fill it with just people detoxing. They’d lay beds on the floor and have thirty or forty people detoxing, super sick.

Imagine, entire cell blocks full of people with body aches, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, high blood pressure, feeling and looking like total crap.

Alta Langdon: I try and think of what to compare it to and I've only had the flu once and I don't know that I was that sick. They're sick. They 're really sick.

Boiko-Weyrauch: That’s Alta Langdon. She runs the health services at the jail.

Langdon: The average person, it makes you think why would you do it again? But the power of addiction is just so strong, it doesn't make sense to somebody who doesn't abuse drugs.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Alta is showing me the medical care the jail provide inmates and the jail’s new programs to tackle opioid addiction.

Langdon: It's our job to be empathetic to the symptoms and continue to just treat them every time and hope that, one day, it’ll click and they’ll find a smoother, gentler path.

Boiko-Weyrauch: On this visit, we go all over the jail. To move from one secure section to another, we stand in front of thick doors with a camera overhead. We look up and wave.

Apparently you should always be very nice to those folks who control the doors from the other side of that camera.

I guess they like us OK, because the door opens and shuts behind us.

This jail’s not a cozy place. Everywhere I look is cinder block walls painted white, fluorescent lights, and linoleum floors.

As we walk around, we peek in through the windows of the cells where people are detoxing. In some, there’s just one inmate—in others there are a few—usually lying down wrapped in a green blanket in a deep sleep.

On this tour with Alta, I can’t help but notice that she keeps talking to me in a really soft voice— almost whispering

Langdon: Everything echoes in here, so we really try and be mindful about what we’re saying and who we’re saying it to and not disturbing people as they’re trying to heal.

Boiko-Weyrauch: The jail is using Suboxone medication to help make detoxing from opioids easier in the jail.

Suboxone compared to other medications for opioid withdrawal.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH / FINDING FIXES >>

Boiko-Weyrauch: Under the old system, inmates were still getting medication. Actually they were getting more medication. Alta shows me a cart with a cornucopia of drugs that an inmate might take for opioid withdrawal.

Langdon: Here's the suppository for Promethazine, the antacid, the ibuprofen for body aches, maybe some Tylenol for body aches, a vitamin, and the magnesium to help with the muscle agitation and helps relax a little bit. There's also Loperamide there.

Boiko-Weyrauch: What’s Loperamide for?

Langdon: That’s for the diarrhea.

Boiko-Weyrauch: But under the new approach, they’re trying out just giving inmates one drug.

Langdon: And then there's Suboxone. So once they take one of these. Usually within two to four hours they're feeling better and by the second day they're cleared from medical housing.

Boiko-Weyrauch: And then the medical staff doesn’t have to watch them constantly.

The Snohomish County Jail is not alone in providing inmates with medication for addiction like Suboxone. A few other jails across the country do it too. Alta says she looked at Massachusetts for example.

Rhode Island’s prison system has a really interesting program too, it’s very comprehensive. And the first year after it was implemented, there was a 12% drop in statewide overdose deaths.

Also, other jails around the US give inmates an opioid blocker shot called Vivitrol or Naltrexone.

Research on using addiction medicine with inmates shows that it can be effective in helping people continue drug treatment after they get out of jail or prison. You can look in our show notes for links to that research.

At the Snohomish County jail, inmates can choose to start taking Suboxone around a week before they’re released. That’s to protect them from the urge to start using drugs once they leave jail.

So far, the jail’s Suboxone programs are new and fewer than 100 inmates have gone through them—so they don’t have much data yet to evaluate the effectiveness.

One important point though is that it’s more than handing out pills.

Langdon: It’s not as simple as just giving them a medication and releasing them. It’s a matter of connecting them to the tools they need to be successful as they leave.

Boiko-Weyrauch: So the jail’s program includes drug therapy groups behind bars and someone at the jail door to pick up people when they’re released.

Getting people help when they first leave jail is super important.

Once someone goes off opioids and gets out of jail or prison, it can be very risky for them. Their tolerance to opioids goes down, so if they go back to drugs it’s easier to overdose and die.

Langdon: So the officer working in here would also be good to talk to.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Alta brings me over to a jail deputy walking up and down in front of the cells.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Hi.

Teresa Porter: Hi.

Boiko-Weyrauch: I love your tattoos.

Porter: Oh, thank you.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Her forearms are covered and mostly criminal justice-themed. The pink handcuff tattoo sticks out—it was her first.

Teresa Porter’s pink handcuff tattoo.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH/FINDING FIXES »

Porter: Because I had pink cuffs here and they banned them so I put them on my wrist —and then it just kind of escalated from there. I love guns, I love knives, I’ve got my kid’s finger prints here.

Boiko-Weyrauch: The officer’s name is Teresa Porter, and the drug problems in this community are not just part of her professional life, they’re personal.

Her 23-year-old son just got out of federal prison. She says he’s addicted to drugs.

Porter: He's back at home with—I never thought I'd have to you know have a kid back at home at twenty three and hopefully in recovery for good this time.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Are you afraid he might use again and overdose because his tolerance has gone down?

Porter: Yeah. Oh, I'm terrified. Every day I worry about whether he's going to stay clean or go back to his old ways. So, I know it's a struggle for him. And it is, as for every addict, they think about it daily. Even though he's clean right now and he says he feels good just like him slipping up before he just can't stop thinking about it.

Boiko-Weyrauch: How is that for you as a mom?

Porter: Oh, it's tough. It's toughest thing I've ever had to do is go through this with him. So, it's not easy. I had—on that level being a parent it's been—it's been different seeing it—my son go through it because now I'm a parent going through it so I think about the people that are in here and you know they also have parents that probably worry about them.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Teresa gives the inmates what she calls her mom speech, like what she tells her son.

Porter: What are you doing? There's more to life than drugs, you know your parents don't want to have to bury you. I don't want to bury my kid. My son has so much potential as do, probably, most of these people and I just would hope that someday they'd be responsible members of society and you know, have a dream or goal.

A cell in the Snohomish County jail.

CREDIT: ANNA BOIKO-WEYRAUCH / FINDING FIXES. >>

Boiko-Weyrauch: Outside of work, she’s involved with a group for family members of people with addiction.

At her day job, she does a lot of walking, around the ward and peaking in windows. Checking up on inmates, to make sure they’re OK.

Porter: And that's it. I do this every half an hour between letting him out for the phone get him out for court.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Each step going into her fitness tracker.

Porter: Stuff like that.

Boiko-Weyrauch: So you get your steps in every day.

Porter: I do. Yes. Yep.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Here’s someone who might have received Teresa’s Mom Speech. You know, the one where she tells inmates there’s more to life than drugs? Meet Heather Alexander. Heather was in Snohomish County jail, got drug counseling there and got on Suboxone. She’s a young woman from a small town in Snohomish County known for its history of logging and meth. She has long blonde hair, and every time I see her, her makeup is immaculate. She used to be homeless and addicted to heroin.

Boiko-Weyrauch: What was it that made you say I don't want to use anymore and I'm not going to use anymore?

Heather Alexander: I have a son—a beautiful four-year-old son, Christopher Aidan. I've wasted so much time and so much life in that world where—it leads nowhere but down. It doesn’t matter how high you come up or how good you do—and I don't want that. I don't want to get deeper and deeper until I'm dead or locked up forever. You know? I want life I want to be a mom to my son. He’s what matters most.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Her son is now living with her father, in her hometown. Heather has been on Suboxone for three months at this point. I meet her at the Ideal Option clinic in Everett. It’s the one where we spent a lot of time at in Episode One.

Alexander: I went to jail for about seven months. I got caught with drugs. And while I was in there, there was the program that we're doing for the Suboxone and I did in-jail treatment classes and got signed up for them to come pick me up the day I got released in the morning so Jodi was there waiting for me.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Jodi is Jodi Aponte a chemical dependency counselor.

Alexander: And she, I mean, I had nothing but the summer clothes on my back that didn't fit because I gained thirty pounds and she gave me a coat and she drove me here and we got everything taken care of.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Jodi works in the jail doing drug counseling and also meets people as soon as they’re released. Jodi and Heather know each other from Jodi’s drug treatment groups in the jail. Right now, she’s sitting next to Heather, and I want to say reminiscing, but that’s not really the right word. They’re talking about the time a few months ago when Jodi picked Heather up from the jail.

Jodi Aponte: She had spaghetti straps on a rainy cold day I took my gray sweatshirt and I just washed it and I'm like oh my God put this on. Like black yoga pants.

Alexander: And my fat’s like all spilling out of them.

Aponte: They were way too small. And she had flip flops. Wasn’t it even flip flops?

Alexander: (Laughing) They were flats.

Boiko-Weyrauch: On a good day, I think Pacific Northwest winters are best described as clammy. After Jodi picked Heather up, they picked up her Suboxone prescription and they made a plan of where Heather was going to go that night so she didn’t go out and use heroin.

Alexander: It made a huge difference. I probably wouldn't be sitting here.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Where do you think you would be?

Alexander: Using in the streets. Yeah because I—you're not going to run into anybody else out there except for other people you know in the same situation. What are you going to do? It’s cold.

Aponte: They're automatically triggered.

Boiko-Weyrauch: This is Jodi again.

Aponte: When they take one step out that door they’re automatically feeling like they're in withdrawals because every other time they've been on the street it's been either to get their drug of choice or using. So they hit that street and their body feels like it's it in withdrawls. They start to really get kind of antsy. And so, like if I wouldn’t have been standing next to her, saying, “Ok here’s where we’re going,” she would have—who knows where she would have ended up.

Boiko-Weyrauch: By the time we taped this episode, it was almost eight months after that meeting. Heather has an apartment, a job, and is still off drugs.

For a lot of the people we talked to who use drugs or who are in recovery, jail time is a part of life. The latest national stats on jail inmates bear this out. In local jails, over 70 percent of inmates have a diagnosable drug or alcohol addiction. Not because they’re bad people. Yes, heroin is an illegal drug. So just having some on you can get you a felony—in Washington state anyway.

But here’s another key point, often, drug addictions are expensive. A few researchers have done surveys of drug users to figure out how much it costs per day. A study in Detroit a few years ago found on average, a user spent about $60 a day. So let’s calculate, 60 bucks a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. That’s almost $22,000 dollars.

Female users spend even more. They averaged 80 bucks a day on heroin. That’s a lot of money. So, it’s not surprising that the survey found a big chunk of their income came from crime, like selling drugs or prostitution.

One more thing before we go, let’s check back in with Hallie and Monty. They’re the couple in their 20s who stopped using drugs on Valentine’s Day, 2018. They’ve had their share of court cases and jail time. The memories are still fresh. Hallie even had a weird dream about Monty the other night.

Hallie Martin: I had a dream that he literally like went to jail and I was like stuck by myself. His bail was like a thousand dollars. So I was trying to get all this money together and it was like taking me a while. I didn’t just have a thousand dollars I could get so I had to go to different people. And I used to have a MacBook and we pawned it and like in my dream, the only way to get the rest of the money to get him out of jail was to pawn my MacBook so I was, like, sad. So, I got him out of jail, and then, like, I woke up. That was like, wow, that felt way too real.

Boiko-Weyrauch: But since February, they’ve been trying their darndest to move beyond that old life. Monty recently got a union job as a carpenter. Hallie and Monty have moved out of the hotel where they were living into a two bedroom apartment. Monty hoists a bag of trash into a dumpster in the parking lot. He’s 25 and this is the first apartment he’s ever had.

Monty McGary: I feel pretty accomplished. You know looking at my past, you wouldn't think I'd be able to achieve all that all the things that I've achieved so far. Like with a job and an apartment and a car. When like one point I was homeless and didn't have anything but like a backpack with a few clothes.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Now the couple is hardcore nesting. Hallie pulls pre-made cookie dough out of a bag and puts a few chunks in the oven to bake. This is a routine for her. Hallie loves warm cookies. Their silver kitty Luna is making herself at home too. She laps up the stream from a small plug-in waterfall.

Martin: Monty bought this at Wal-Mart for ten bucks and it's so loud like—it sounds like a car motor.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Hallie shows us their second bedroom.

Martin: But I decided I was going to do like gray and blue and white for like the baby colors.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Surprise! She’s pregnant! Hallie and Monty are expecting a baby girl. They found out a few months ago, during a clinic visit to treat her opioid addiction. This is the longest she’s ever been off drugs since she got addicted. Monty is getting his game face on. He’s pushing back against any urges to use drugs.

Hallie Martin and Monty McGary setting up a nursery in their home.

CREDIT: LEAH NASH FOR FINDING FIXES »

McGary: Just even today I got a friend request from like old friend that I used to, you know, use with and I just thought about all the—all that past. And like sometimes I just want to escape, you know? Sometimes I feel emotions I don't like, or I’ll feel pain and I just want to escape, and that's a trigger. But we can't, you know, we have a baby on the way. It's time to grow up and be serious and like, I’ve—actually I have lives depending on me now.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Hallie gets up to take the cookies out of the oven.

Boiko-Weyrauch: When you have uncomfortable feelings now what do you do how do you deal with them?

McGary: I just play the tape through. On like what will happen if I use. What I'll lose and who the people I'll affect if I use and—like my track record shows that I can’t just like use drugs like one time. That it just repeats itself in a vicious circle and I lose everything.

Boiko-Weyrauch: He plays the tape through in his head. Starting at using drugs until the very end. That tape never ends well. Instead, Monty says he dreams of being a good father. And he’s looking forward to the day he’ll have a house with a white picket fence, kids, dogs. And as he says, a normal, boring life.

When we produced this episode it was about nine months after Snohomish County started treating the opioid epidemic as a state of emergency on par with a natural disaster. They started by giving themselves a one year timeline to work with. So in a few months, they’re going to look back and see how they’ve done.

Here’s Shari Ireton. She’s with the sheriff’s department and she also represents the county’s efforts on opioids.

Shari Ireton: Sometimes we joke a little, well, we’ll just wrap this thing up by November. None of us believe that that is even possible. It’s as complex as people are.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Snohomish County hasn’t solved the opioid epidemic. But other communities and state leaders are looking to them to see how good their efforts have been.

In these past five episodes we’ve broken that effort into pieces and gotten to know what’s involved. We’ve looked at a few ways people here are trying to tackle the epidemic. And there’s so much we haven’t been able to talk about.

In future episodes we want to keep looking at solutions to the opioid epidemic and bring you lots more stories. We want to get personal and meet more people finding solutions in their own lives. We want to get the big picture: What are other communities, other states, even other countries doing that works?

And we hope you stay tuned and send us your stories and ideas. You can email us at fixes@ findingfixes.com.

For now, that’s the first season of Finding Fixes. Thanks so much for listening.

We’ll be back with more episodes just as soon as we can make them!

Norris: This episode was produced by Anna Boiko-Weyrauch, and me, Kyle Norris. Finding Fixes is a project of InvestigateWest, a journalism non-profit, reporting on public health, the environment, and government accountability.

Julia Drachman is our producer. Alisa Barba is our editor. Joan Caine is our fairy godmother. Help from Paul Kiefer.

Boiko-Weyrauch: Music by Jake Weholt, Josh Woodward, and Jason Shaw.

Norris: You can find us on social media and online at Findingfixes.com. Leave us a review on iTunes. Send us a message at fixes@findingfixes.com